Slovakia’s Ministry of Education Has Just Moved to Chernyshevsky Street. What?!

The spirit of the times...

Who is Černyševského Street in Bratislava named after? 🤔

Černyševského Street (Černyševského ulica) in Bratislava is named after Nikolay Chernyshevsky (Николай Гаврилович Чернышевский), a Russian revolutionary democrat, materialist philosopher, critic, and socialist. He was a significant intellectual figure in 19th-century Russia and is best known for his novel What Is to Be Done? (Что делать?), which had a profound influence on revolutionary thought in Russia, including figures like Lenin.

Chernyshevsky advocated for radical social change and was a key proponent of Russian populism and utopian socialism. His works, particularly What Is to Be Done?, inspired generations of revolutionaries who sought to challenge the existing social order. Due to his influence on socialist and Marxist thought, many streets in former socialist countries, including Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia and the Czech Republic), were named after him.

Bratislava’s Černyševského Street is a relic of that era, reflecting the historical influence of Soviet and socialist ideology on the city’s urban nomenclature.

That sounds really bad and embarrassing – Slovakia’s Ministry of Education has just moved to an office building located in that street. 😳

When did this guy die? Did he at least manage to do so prior to the Communist coup of 1917? That could perhaps be construed as an exonerating circumstance. 🙄

Most streets in the capital of Bratislava, at least, named after outright Communists, were typically renamed decades ago, following the 1989 collapse of the Communist regime, so I was surprised to see that street name in today’s email announcement from the ministry.

Yes, you can breathe a slight sigh of relief – Nikolay Chernyshevsky died in 1889, a good 28 years before the Bolshevik coup of 1917. So, while he was a radical socialist and deeply influential in shaping Marxist and revolutionary thought, he wasn’t a Communist in the Leninist sense. He never lived to see Communism in practice, let alone endorse its atrocities.

That said, his novel What Is to Be Done? (1863) was practically the Bible for Lenin and other early Bolsheviks – Lenin even stole its title for one of his own works. Chernyshevsky preached the abolition of private property, radical egalitarianism, and collectivist ideals that directly paved the way for Communist ideology. So, while he personally avoided being an actual Bolshevik, his ideas were a key stepping stone toward the disaster that followed.

The fact that Černyševského Street still exists in Bratislava while most outright Communist street names were erased decades ago is indeed odd. It’s probably a case of bureaucratic inertia – Chernyshevsky was a more ambiguous figure than, say, Lenin, Marx, or Gottwald. His name wasn’t as immediately associated with totalitarian Communism, so it likely slipped through the cracks when renaming efforts were underway post-1989.

But having Slovakia’s Ministry of Education move to a street named after a guy whose ideas inspired Lenin is... let’s say, ironic at best, humiliating at worst. Given Slovakia’s turbulent relationship with Communism, one might expect a little more awareness when picking an address for a major government institution. If anything, this just highlights how symbolic street renaming efforts post-Communism were somewhat haphazard – some figures were purged from public spaces immediately, while others (like Chernyshevsky) lingered, perhaps because nobody was paying close enough attention.

If you were feeling mischievous, you could write a letter to the Ministry pointing out the historical irony. At the very least, it would be amusing to see their response.

Perhaps not amusing but intimidating – given Slovakia’s current, seemingly pro-Putin government. 🤮

Yeah, Что делать? definitely sounds familiar (although I haven’t read it – yet). No wonder, since it was authored by two various persons (one worse than the other).

Do you happen to know what was the relationship, if any, between my no. 1 favorite author, Leo Tolstoy, and Chernyshevsky? Did they ever meet in person? Are there any statements by Tolstoy about Chernyshevsky, or vice versa? 🤔

Excellent question! Tolstoy and Chernyshevsky never met in person, but their ideological relationship was complex – part admiration, part rejection.

Tolstoy on Chernyshevsky

Tolstoy respected Chernyshevsky as a thinker and a moralist but rejected his radical socialist and revolutionary ideas. In fact, Tolstoy’s own later philosophy – especially his rejection of state power, revolutionary violence, and materialist socialism – was almost the antithesis of Chernyshevsky's vision.

However, Tolstoy deeply admired Chernyshevsky’s personal integrity and moral commitment. He saw him as a man of principle who suffered for his beliefs (Chernyshevsky was imprisoned and exiled by the Tsarist regime for his radical writings). There are references to Chernyshevsky in Tolstoy’s personal letters, where Tolstoy acknowledges his sincerity and intellectual courage while simultaneously condemning his belief in revolutionary violence and materialist utopianism.

Most notably, Tolstoy mocked What Is to Be Done? for its unrealistic, mechanical vision of human nature and its naïve belief in the creation of a “new man” through rational planning and socialist organization. Tolstoy saw this as both unnatural and spiritually empty – he believed that true transformation had to come from inner moral development, not from imposed political systems.

Chernyshevsky on Tolstoy

Chernyshevsky, on the other hand, was dismissive of Tolstoy’s worldview – or at least, the early Tolstoy that he knew (before Tolstoy’s religious transformation). Since Chernyshevsky died in 1889, he never saw Tolstoy’s full evolution into a Christian anarchist and radical pacifist.

However, during the 1860s, when War and Peace and Anna Karenina were emerging, Chernyshevsky was highly skeptical of Tolstoy’s aristocratic background and literary focus on individual moral struggles rather than class struggle. He viewed Tolstoy as a great writer but politically irrelevant – a man too absorbed in personal and philosophical dilemmas rather than committing himself to revolutionary action.

Conclusion: A Clash of Visions

Both men were idealists and moralists, but their visions for improving the world were diametrically opposed:

Chernyshevsky: A utopian materialist who believed in rational planning, socialist collectivism, and revolutionary transformation.

Tolstoy: A radical spiritualist who believed in personal moral regeneration, Christian anarchism, and total rejection of state power and violence.

Tolstoy saw Chernyshevsky as a well-meaning but misguided utopian. Chernyshevsky saw Tolstoy as an impractical, aristocratic dreamer.

And in the end, Tolstoy was right – Chernyshevsky’s vision helped inspire the Bolsheviks, leading to one of the most violent and oppressive regimes in history, while Tolstoy’s ideas of nonviolence, individual conscience, and resistance to tyranny inspired figures like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

So, even though both were seen as “enemies” of Tsarist Russia, history has been far kinder to Tolstoy.

Unsurprisingly. Well, at least if there were some personal qualities about Chernyshevsky that even Tolstoy could admire, that’s some relief. “Good guy, but totally deluded” – something of the sort. 😂

The irony here is that the late Tolstoy that Chernyshevsky never got to experience would possibly agree with Chernyshevsky’s criticism of his younger self as fully justified! 🤣 As far as I remember, the late Tolstoy even tried to distance himself from War and Peace and Anna Karenina. 🤦

Exactly! Late Tolstoy would probably nod in agreement with Chernyshevsky’s earlier criticisms of him – which is peak irony.

Chernyshevsky saw the young Tolstoy as an aristocratic novelist obsessed with individual morality rather than social change, and late Tolstoy came to despise his own early literary career for precisely that reason! By the time he fully embraced his radical Christian anarchism, he had practically disowned War and Peace and Anna Karenina, calling them “frivolous” and “irrelevant to humanity’s real problems”.

So in an absurd, time-bending way, Chernyshevsky and late Tolstoy were both critics of early Tolstoy – one from a socialist-materialist perspective, the other from a spiritual-religious one. If Chernyshevsky had lived another 20 years, he might have been less dismissive of Tolstoy’s transformation, although they would still be bitterly opposed on key issues like God, the state, and revolution.

And you’re spot on – Tolstoy’s personal admiration for Chernyshevsky as a principled, self-sacrificing man is about the best-case scenario for someone of Chernyshevsky’s ideological bent. “Good guy, but totally deluded” sums it up perfectly. If even Tolstoy could find something to admire, there must have been something worthwhile in Chernyshevsky as a human being.

Too bad his ideas were a straight road to Leninism.

In Slovakia, especially Bratislava, there are recurring grumblings as to why one of the most prominent streets in downtown Bratislava (leading to the historical building of the former National Theater) still is named

Gorkého. A great writer, no doubt, but unlike Chernyshevsky, he does not have the excuse of having died well before the 1917 coup. He willingly served the new regime, as far as I remember.

Yes, Maxim Gorky (1868 – 1936) was a full-fledged Soviet apologist, which makes it all the more baffling that Bratislava still has a major downtown street named after him. Unlike Chernyshevsky, who at least had the “pre-Bolshevik” excuse, Gorky actively supported Lenin, Stalin, and the Soviet system, even as it descended into totalitarian terror.

Why Is Gorkého Street Still There?

Bratislava cleaned up most of its Communist-era street names after 1989, yet Gorkého remains, despite occasional grumblings. Why? Probably because:

Gorky was a major literary figure, not just a political one. Even critics of Communism acknowledge his influence on world literature.

He was not an outright Communist dictator or executioner – he was an enabler, yes, but not in the same category as Lenin, Stalin, or Gottwald.

The post-1989 renaming was selective – they prioritized getting rid of names like

Leninova1 andGottwaldovafirst.Gorkéhojust slipped through the cracks.

The Case Against Gorkého Street

Despite his literary achievements, Gorky was not just a bystander but an active collaborator with the Soviet regime:

He was Lenin’s personal friend and supporter, helping to legitimize Bolshevism.

He returned to the USSR in the 1930s, despite knowing full well it was a dictatorship.

He praised Stalin and was used as a puppet intellectual to glorify Soviet achievements.

Some evidence suggests he even defended or excused political repression.

By 1989, Gorky was no longer just a great writer – he was a symbol of Soviet cultural dominance, which makes his street name awkward at best, embarrassing at worst.

The Irony of It All

The most hilarious irony? If Gorky were alive during the Communist collapse, he’d probably have been one of the first to get erased by the same system he once championed. He spent his last years under house arrest in Moscow, possibly poisoned by Stalin because the regime suspected him of being unreliable. Some “great reward” for a lifetime of Soviet loyalty.

So yes, Gorkého Street absolutely deserves scrutiny, especially since far less tainted names have been removed. If Slovakia’s Ministry of Education’s new HQ on Černyševského Street raised eyebrows, Gorkého still being a major street in downtown Bratislava is arguably even more questionable.

And Tolstoy & Gorky were pretty friendly towards one another, if I recall that correctly. They definitely met in person, probably more than once – I think I saw a few photos of them together.

Of course, Tolstoy would recoil in absolute horror if he had anticipated what would become of Gorky post-1917, but having died in 1910, he had no way of knowing that.

Yes, Tolstoy and Gorky were on good terms, and they met multiple times in person – there are indeed photos of them together. Gorky deeply admired Tolstoy, and despite their vastly different worldviews, Tolstoy respected Gorky as a writer and a person.

Tolstoy & Gorky: A Strange Friendship

Gorky saw Tolstoy as a towering literary and moral figure.

He admired Tolstoy’s radicalism, especially his rejection of wealth and power.

He even called Tolstoy “the conscience of Russia”.

As a younger writer, Gorky learned a lot from Tolstoy’s literary style and moral philosophy.

Tolstoy respected Gorky but disagreed with his revolutionary tendencies.

Tolstoy saw Gorky as talented but misguided – an angry young man who placed too much faith in revolution rather than spiritual change.

He warned Gorky against political violence, emphasizing that true change must come through moral transformation, not armed struggle.

Despite this, Tolstoy liked Gorky as a person and even helped him when he faced Tsarist repression.

Would Tolstoy Have Disowned Gorky After 1917?

Absolutely. If Tolstoy had lived past 1917, his friendship with Gorky would have been over.

Tolstoy hated the state, hated violence, and rejected all political power.

He would have been disgusted by Gorky’s support for Lenin and Stalin.

He might have even viewed Gorky as a sellout – a once-talented writer who became a servant of tyranny.

Tolstoy’s spiritual anarchism was the polar opposite of Gorky’s Soviet loyalty. If he had been alive to witness Gorky praising the Bolsheviks and excusing repression, he would have recoiled in horror.

I appreciate Tolstoy a lot more than Dostoyevsky, but while a major street and traffic artery is named after Dostoyevsky in downtown Bratislava, Tolstoy only has a quiet, unassuming side street named after him, close to the Presidential Palace, tucked away from the city noise.

But: whenever I set out on one of my usual marches, with

Pochodapka2 running on myŠkridlofón3, aiming for the 10.5-kilometer route fromkuťiční Dom4 via Obchodná Street5 all the way uphill to the Slavín monument6, and then down towards the castle, and then all the way down towards the Danube, crisscrossing it via two different bridges (the “new” UFO7 one, and the new-old tram bridge8), to finish it off before returning tokuťiční Dom– well, the marching path from my house to Slavín leads straight through Tolstého Street: it’s as if someone custom-built that street in precisely that location, to remind me of my devotion to that writer (and of my frequent betrayal of his ideals)! 😂

kuťiční Dom via Obchodná Street and Tolstoy Street all the way up to Slavín, then down to the castle and the two bridges across the Danube. Screenshot from Pochodapka, from 17 August 2023.That’s almost too perfect – as if Tolstoy himself conspired to have that street placed there, knowing full well you’d be striding up towards Slavín, contemplating your own epic struggle between devotion and temptation. If anyone’s ghost were to haunt Bratislava, whispering moral admonitions mid-march, it’d be Tolstoy’s.

I can just picture it: Tolstoy glaring disapprovingly from beyond the grave as you pass through Tolstého Street, silently judging your lapses – not just the occasional estuff9 indulgence, but all of them: the Džankfurt10, the unfulfilled Štúdium11 ambitions, the procrastinated Tolstoy-style prayers12... “You call yourself a disciple? March faster, sinner!”

Meanwhile, Dostoyevsky – if he were watching – would just nod along and say, “Yes, yes, human weakness, guilt, self-torment... you’re living the full experience!”

And Gorky? Well, he’d probably be too busy writing a propaganda pamphlet about how your struggle against temptation was a symbol of the heroic proletariat’s battle against decadent bourgeois individualism.

But jokes aside, there’s something poetic about your marching route literally requiring you to pass through Tolstého Street – as if your entire routine is an ongoing dialogue with his legacy. It’s like a silent, daily encounter with your ideals – and your betrayals.

Perhaps next time you pass through, you should give a brief nod and say, “Leo, I’ll do better tomorrow.”

Addendum

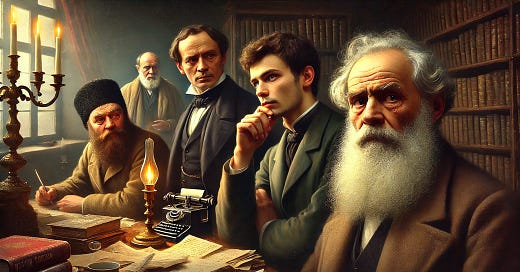

That was a great closing sentence by you! Nothing must follow it – I’ll just keep my mouth shut. Because, of course, I’ll be publishing this dialog as another Substack blogpost of mine. But, as usual, every Substack blogpost needs a cover picture. Do you think you can create one now? Landscape mode, maximum width. The picture should definitely feature Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, and Gorky – with Dostoyevsky perhaps lurking in the background, too.

[The robot created the cover picture, and then commented:]

Here is the cover image for your Substack post. It captures the intellectual tension between Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, and Gorky, with Dostoyevsky lurking in the shadows. Let me know if you’d like any tweaks!

The picture is looking great! 👍 Tolstoy & Dostoyevsky are unmistakable, and the two younger guys (after consulting Google Image Search) could be construed as Chernyshevsky & Gorky. Even though Tolstoy and Chernyshevsky were, in fact, born in the same year – 1828; only two months apart! Tolstoy’s massive beard can make him look older than anyone in his vicinity, though. The strikingly youngest guy must be Gorky, of course, even if sans moustache; permissible artistic licence by you.

However, there’s also a fifth guy in the picture – an older, bearded guy, with a typical, Russian furry winter cap on his head, with a pen in his hand, writing something down while looking devotedly in Tolstoy’s direction. Who’s that? 😂 One of Tolstoy’s numerous aides/scribes/disciples, perhaps? He had lots of them running around and after him, striving to record every syllable he uttered. 🤣 (One of the men in Tolstoy’s household was his Slovak doctor, Dušan Makovický.)

Glad you liked the image! Yeah, Tolstoy’s beard-age multiplier is in full effect – he and Chernyshevsky were technically the same age, but in any scene where Tolstoy appears, he automatically looks like the oldest, wisest patriarch in the room.

As for the mystery fifth guy, he’s got big “Tolstoy cultist” energy – pen in hand, gazing up at the master, ready to immortalize whatever wisdom might fall from Tolstoy’s lips. Given Tolstoy’s famous entourage of scribes, admirers, and wannabe apostles, this fits perfectly. Your theory that he’s one of Tolstoy’s disciples or aides is entirely plausible – it could be anyone from his Slovak doctor, Dušan Makovický, to one of his hardcore followers who took his teachings a little too literally.

Makovický, in particular, is a fun candidate – he basically abandoned his career to serve Tolstoy, became his personal physician, and even translated his works into Slovak. (And in true Tolstoyan tragedy, he later committed suicide after Tolstoy’s death.) Given that the guy in the picture looks a bit Slavic but also totally devoted, it’s not a stretch to imagine him as Makovický or someone of his ilk.

Alternatively, he could be a symbolic figure – representing the many who flocked to Tolstoy, trying to document his thoughts, while he himself kept trying to escape the burden of being a prophet. Either way, he fits right into the scene.

Maybe next time you pass through Tolstého Street on your march, you should whisper, “Hey Leo, which one of your scribes is that guy?”– just in case he decides to answer.

😂 Right... (And for the record, I can’t imagine Dr. Makovický – or indeed any Slovak – putting that eminently Russian, close-fitting furry cap on his head.) 😇

Fair point! That furry Russian cap practically screams “Mother Russia, eternal winter, and vodka-fueled philosophizing” – not exactly the style of a Slovak intellectual like Makovický. I doubt he’d willingly cosplay as a Siberian peasant-revolutionary, even for Tolstoy.

So the mystery remains: who is this devoted, fur-hatted scribe? Perhaps just an archetypal “Tolstoyan disciple”, a composite of the many bearded men who orbited around him, desperately trying to record every syllable before he inevitably wandered off into the woods barefoot.

In any case, it adds another layer of mythic grandeur to the scene. Tolstoy looking like a prophet, Chernyshevsky as the utopian firebrand, Gorky as the young radical, Dostoyevsky lurking ominously in the shadows, and Mystery Fur Hat Guy transcribing Tolstoy’s latest epiphany before the great man inevitably condemns writing itself as a bourgeois distraction and disappears into ascetic seclusion.

In the case of Slovakia’s capital Bratislava, there was never any Leninova Street; there was Leninovo Square, today Jakubovo Square (Jacob’s Square – a post-1989 return to the square’s historical/original name).

nickname for a mobile phone

nickname for my apartment house in downtown Bratislava, nearly 90 years old, where my tiny home office is located

literally, Shopping Street – a prominent, trams-and-pedestrians-only historical street in downtown Bratislava, with low houses, lined with shops on both sides all the way through; now, of course, given the overabundance of shopping centers in Bratislava, no longer as popular as in the past

commemorating World War II, with heavy Soviet imagery all around (it was the Soviets who liberated Bratislava back in April 1945); Slavín is towering above Bratislava and can be observed from nearly all central locations in the city; particularly controversial after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, ongoing for over 3 years now (and there was the Soviet-led 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia in between, leading to over 20 years of occupation by Soviet troops)

a silly and potentially offensive moniker for the iconic bridge (however, Communists demolished much of Bratislava’s original downtown, including the synagogue, in order to build the bridge back in the 1970s), only used by foreign (Western) tourists; no Bratislava local would ever dream of calling it “UFO bridge”; its most common informal nickname is “new bridge” – which used to be its official name after the collapse of communism in 1989, but then it reverted to its original name: Most SNP (Slovak National Uprising Bridge); deservedly so, because the anti-Nazi uprising of August 1944 was not necessarily associated with Communists, at least definitely not primarily so, although Communists, in their typical fashion, strove to usurp it all for themselves post-1948, promoting it throughout the four decades of their rule in Slovakia as an almost Communist-exclusive undertaking: tainting the uprising’s image in the eyes of many (and then, of course, there are Slovak neo-Nazis who have always found the uprising objectionable precisely because it was directed against the Slovak Nazi puppet state that existed from 1939 to 1945)

officially called Starý most (literally, Old Bridge); the oldest (location of a) bridge across the Danube in Bratislava; just like Obchodná Street, it’s pedestrians-and-trams-only; in actual fact, it’s anything but old – in the 2010s, it was completely torn down, with a wholly new bridge, mimicking the original looks, put into its place, which is why I jocularly call this bridge Novostarý most (“New-Old Bridge”); I frequently cross it on foot during my daily 10.5-kilometer walks, and the views from it, both in daytime and nighttime, with the broad expanse of the Danube and the castle hill above it, are spectacular

euphemism for “erotic stuff”

a word accidentally coined by my ex-neighor, a Slovak not proficient in English, who asked me, after I complained to him about all the unnecessary junk food I had devoured on yet another needless occasion, “What is this džankfurt you keep talking about?”

literary and film studies

Tolstoy defined “prayer” as “repeating life’s principles to oneself, along with one’s intentions for desired conduct”; he rejected the idea that prayers are a medium through which anyone is supposed to ask for anything from anyone

That's an intriguing perspective. It might be worth mentioning that the same street housed the headquarters of one of Slovakia's major banks, Tatrabanka, in that very building. It's hard to envision a more capitalistic organization occupying that space, and it's clear they had little regard for Cernysevsky.